JONG SOOK KANG

Ceramic Sculptor with Passion

web: jskceramic.org / email: jskceramic@gmail.com / (201) 417-8789

2023 Paris Koh Fine Arts Gallery, NJ

2005 Tongin Gallery, New York

2000 “Space & Time”-Old Church Culture Center NJ

2000 Clay Art Center, Port Chester New York

1999 Dai Ich Gallery, NYC, New York

1998 Bergen Museum of Art & Science, NJ.

1998 International Ceramic Symposium-Novohradsk Gallery, Lucenec, Slovakia

1998 One Gallery, Montclair State University, N.J

1996 Bratislava Museum of Slovakia

1994 Hurr’s Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2023 Sculptor Affiliates of ACNJ -Clifton Art Center,NJ

2022 Sculptural Affiliates of ACNJ -Barron Art Center, NJ

2022 Paris Koh Fine Arts-”Circles-Centrifugal & Centripetal

2021 FIABCN The Museu Maritim (Maritme Museum) in Barcelona

2021 2 person show -The Korean & American Association

Of Greater, NYC

2020 3 person show “Friends” -The Museum of Russian Art, NJ

2019 ” International Cntemporary Art Fair of Athens, Greece” – Jappeion Mansion

2019 “Material Transformation” Sculptor Affiliates Belski Mesuem – NJ

2019 “Beyond Boundaries” – Korean Cultural Center Ny, Gallery Korea.

2018 4 Artists exhibition “Winds” KCC Gallery, NJ

2016 Group exhibition – D’Art gallery in Chelsea NYC

2015 3 Artists exhibition. Dream Rose Gallery NY

2015 “Journey in the Third Dimension” Sculptor Affiliates, Brooklyn Waterfront Artists

Brooklyn, NY

2015 “Life & Limn” 6 artists –Korean Community Center Gallery,Tenafly, NJ

2014 “35 in 350” The story of New Jersey-William Paterson Univ. NJ

2014 “Pixel” – Elga Wimmer (Hyun Contemporary) Gallery, NYC

2014 “Shades of Time” –Queens Museum of Art Partnership Gallery, NY

2014 Sculptor Affiliates of the Art Center of Northern NJ

2014 “Shades of Time” – Korean Culture Service New York, NY

2014 “Korean Contemporary Ceramics” –The Korea Society gallery, NYC, NY

2013 “Introspection” – Tenri Institue Gallery New York City, NY

2013 7th Biannual show “East & West Clay works exhibition-Hunterdon

Museum Clifton, NJ

2012 “An Indoor Sculpture Park” Sculptor Affiliates of the Art Center of Northern NJ.

2011 Group show-Maum Gallery, NY

2010 Woman power-Chun gallery, NY

2010 6th Biannual show “East & West Clay works exhibition-Arts Council of

Princeton, NJ

2010 Sculpture member show-Nothern New Jersey Art Center, NJ

2010 6 person show-Yegam Gallery, New York, NY

2010 “Wind, where are you going” Maum Gallery New York City, NY

2009 “Yes, we are connected” –Space World Gallery, L.I.C., New York

2009 “Composition of Essential Nature” Jun Gallery New York City, NY

2009 “Yes, We are Connected” Space World Gallery, LIC, NY

2009 Contemplation exhibition, Kepco Plaza Gallery Seoul, Korea.

2008 -“Clay, fire-up, Alchemy”-Hammond Museum, New York

2008 -35th Aniversary Scuㅣpture Affiliates show-Belski Museum-New Jersey.

2008 -”5th East & West Clay work Exhibition-Mashiko, Japan. 2007 – Gorge Segal Gallery-Montclair State University,New Jersey 2007 – 1st Asian Contemporary Art Fair-New York.

2007 – SOFA New York

2007 – ” Touch in Women ” A.I.R. Gallery, NYC

2006 – Loveed Fine Art Galley, NYC

2006 – Sculptor Affiliates, The Art Center of Northern New Jersey, NJ

2005 – Space World Galley, L.I.C. NY

2004 – “Fire Works” East & West Works Exhibition-Space World Gallery, L.I.C. NY

2004 – Sculptor Affiliates, The Art Center of Northern New Jersey, NJ

2003 – “100 Years 100 Dreams – Space World Gallery, L.I.C. NY

2003 – “Generation 1.0 ” Korean Cultural Service Center, Washington D.C.

2003 – ” 10 Artists Show – Belski Museum, NJ

2002 -“Gesture of times”-Space World Gallery-Segye Daily Times News

2001 -7 Artist-FGS gallery New Jersey

2000 -Faculty show-Old Church Cultural Center Gallery in New Jersey

2000 -“The Impact of Millennium, 31 Korean Artists for 21 Century” Space World Gallery, New York, U.S.A

2000 -A Celebration in Three Dimensions Sculptor AAC Northern N.J. -Nabisco Gallery, N.J

2000 -“East & West” Cork Gallery N.Y.

2000 -Sculptor Affiliates of The Art Center of Northern New Jersey, Jersey City, N.J.

1999 -’99 East & West Clay Works Exhibition-New York” Soho 20 Gallery, N.Y. 6 artists with Gil Hong Han

1999 -Salute Member show, The Art Center of Old Church Cultural Center, N.J.

1998 -The 10th International Ceramic Symposium in Novohradska Gallery, Lucenec, Slovakia -“Transmission”-De Zaaijer Gallery Amsterdam, Netherlands.

1997 -Soho 20 Group Member’s Exhibition “Happy Return”-Soho 20 Gallery N.Y -Invited Group Exhibition-Korea Gallery N.Y.

-Soho 20 New Member’s Exhibition “Diversions”-Soho 20 Gallery N.Y

-“A Celebration of Korean Art & Culture Town Hall, Queens, NY

-Korean-New York Artist Society-Rotunda Gallery in City Hall, N.J

1994 The Korean Craft Council Group Exhibition- Seoul, Korea

1993 The 9th Jil-Ggol Member’s Exhibition Dong-Bang Plaza, Seoul, Korea

1992 The 8th Jil-Ggol Member’s Exhibition Dong-Bang Plaza, Seoul, Korea

2004-2005 Attended Glass Browing-Urban Glass NY

1998 MA, Graduate School of department of Ceramic Arts

Montclair State University, New Jersey, U.S.A.

1996 Participated in Summer School Graduate Art & Design

Alfred University Alfred, New York, U.S.A

1994, 92 MFA, BFA, Ceramic Seoul National University of Science & Technology Seoul, Korea

After I moved to New York in 1994, I’ve been working as a ceramic

sculptor. I have been in a studio & resident in NJ.

I earned a BFA, MA degree from Seoul National University of Science

& Technology Seoul, Korea. and MA degree from Montclair State

University, NJ.

I had 10 solo shows, including Paris Ko fine Art gallery, Hammond

Museum, NY, Clay art Center NY, Dai Ichi Gallery NYC,

The Art school at Old church, NJ, Museum of Art , Montclair

State University, Tong In gallery NYC. Bergen Museum NJ,

Bratislava Museum of Slovakia, Hur’s Gallery, Seoul Korea.

I had numerous group shows over last 40 years, Korea Culture

Service Center NYC, Queens Museum NY, George Segal Gallery, NJ.

The Museum of Atene, Greece, Hunterdon Art Museum, NJ.

Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art, Japan, Baron Art Center, NJ.

Clifton Art Center, NJ, Korea Society NYC, William Paterson

University Gallery, NJ. Princeton Art Council Gallery, Princeton.

KCC gallery, NJ, Leveed Fine Art Gallery NYC, Tenry Gallery, NYC

Korea Craft Devel. Foundation, Seoul ,Korea, Maeum Gallery, NYC

Marine Museum of Barcelona, Spain. SOFA ,NYC, KIAF, NYC

Belskie Museum , NJ. Washing DC Korean Culture Center. USA

Alfred University, gallery,NY

I served as a charter member of “The East & West Clay Work

Exhibition” as an organizer from 1999 to 2014.

I’ve been a member of Sculptor Affiliates of Art Center, NJ. since

1997.

Reviewed in Int’l Ceramic Monthly 1997, 2004, Korean Ceramic

Monthly 2006

Selected Award

1999 Juried Exhibition“Celebration of Life” Old Church Cultural Center, NJ

1999 The National Juried Exhibition of small works-MSU Art Gallery NJ

1998 The Montclair Craft Guild Competition-Main Gallery of MSU N.J

1997 -The National umlt-media exhibition “Woman 2 Woman”, -Soho Gallery, Pensacola, Fl.

-The National Juried Exhibition of small works-MSU Art Gallery NJ

-The National Exhibition for 1996

-Westmoreland County Community College-Pennsylvania

-Westmoreland Art & Heritage Festival-Pennsylvania

-The 3rd Biennale Fine Art Exhibition of Montclair State University-Westbeth Gallery, New York

1992 -Special prize in The 12th Seoul Modern Ceramic art Exhibition

-Press Center, Seoul, Korea

-The 27th Korea Industrial Design Exhibition-Design Development Center Seoul,

Korea

1991 -The 6th Grand Craft Exhibition-National Museum

Association Design Development Center Seoul, Korea

Attended Workshop, Residency

2004 Summer-Residency, “Snow Farm” New England Craft Pro. Glass Blowing, MA

2000 Residency, with Bob Burch, Glassing Blowing-Vermont

2000 Summer-Workshop Demonstration-Old Church Culture Center, NJ

1998 Summer-Residency, Ziaromat Factory in Kalinovo, Slovakia

1996 Summer-Residency, Duck Jack-ceramic sculptor, Alfred University,

Membership

East & West Clay Work Association 1999-present

Sculpture Affiliates of Art Center, Northern New Jersey, USA {1997-present}

Featured and Reviewed

American Ceramic Dec. 2007

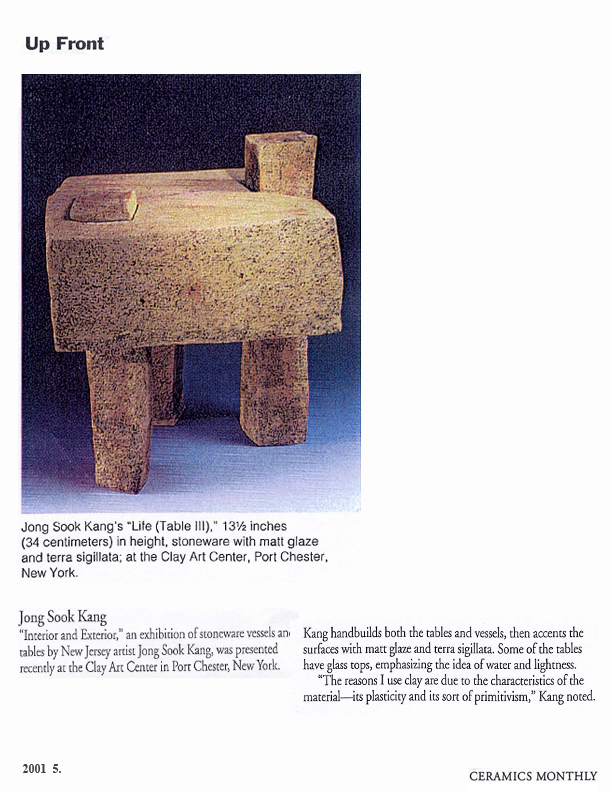

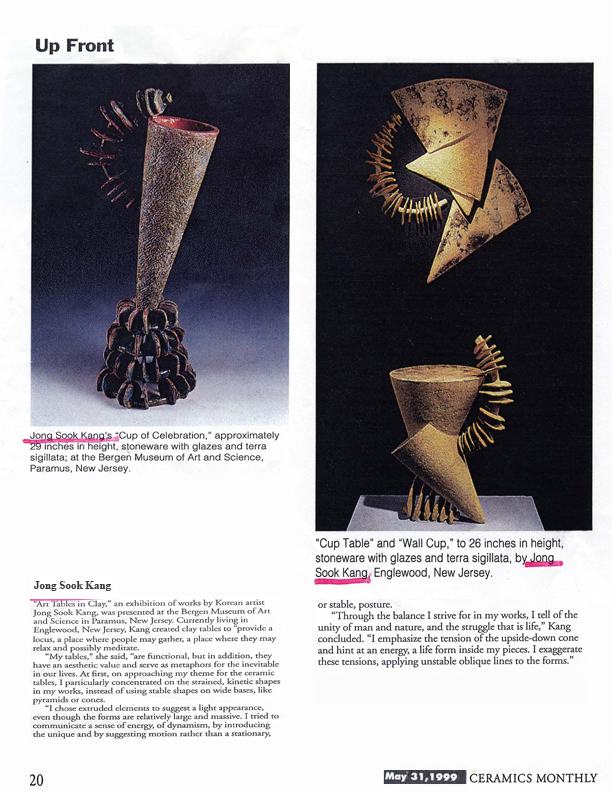

“Up Front” Ceramic Monthly, May 2001

“Up Front” Ceramic Monthly, May ’99

Ceramic Art Monthly Korea, Dec. ’98

Monthly Design Nov. ’98

U.S Monthly Front Line, Feb/March ’97 Collection

Main Gallery in Montclair State University, New Jersey

Bergen Art & Science Museum, New Jersey

Jong Sook Kang: Like a Land of Dreams

By Richard Vine

When the ceramist Jong Sook Kang first came to New York in 1994, two visual experiences—two shocks, really—suddenly imprinted themselves on her mind, at both a conscious and subconscious level. These sights have remained active imaginative resources for her ever since. The first, seen from the plane window, was the city’s vast gridded network of streets, vibrant with traffic. The second was the panoramic sweep of Manhattan’s skyscrapers, viewed across the Hudson River from Kang’s sedate home neighborhood in New Jersey.

Note that these were both views from outside the city proper. Countless new arrivals have had a similar thrill upon landing in New York from sea or air. Most immigrants, though, soon immerse themselves in the dazzling cityscape, establishing a new life amid the throbbing streets and avenues. But that was not Kang’s lot. Yes, she is an artist—trained at Seoul National University of Science and Technology and later Montclair University in New Jersey—but she is also a wife and mother. Like a great many other middle-class Koreans, she made her home in the relatively safe-and-clean environs west of the George Washington Bridge, seemingly a world away from yet in constant sight of a brooding, glistening Gotham.

This is not, however, a simple tale of thwarted dreams. For Kang was able to use her social restraints to channel her creative energy. Over the past 30 years, she has produced a substantial body of work, including a large variety of ceramic apples—popularly identified as the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge in Eden. Desire to know may have condemned Adam and Eve, but it also revealed to them the world we live it. So it is no coincidence that Kang’s most recent solo exhibition was titled “Dreaming Desire.”

The centerpiece of the show was an installation of ten 3½-foot-tall ceramic structures, composed of rectangular plates stacked with space between each layer, disclosing electric light emanating from within. The sculptural group looked eerily like Manhattan’s office blocks and residential towers at nightfall. These objects of Kang’s desire, rife with fantasies of sophisticated, cosmopolitan living, dominated the gallery space and insistently drew visitors’ eyes. But their very seductiveness, and their proud self-assertion, soon caused one to question their silent claims. They resemble a cluster of Le Corbusier high-rises not unlike his Radiant City plan for the center of Paris, mercifully never built. Urbanologists like William H. Whyte have argued that Corbusier’s architectural strategy—lifting multiple living spaces into vertical shafts, clearing out all shops and other low-rise buildings between them to create either greenswards or empty concrete plazas—is actually an assault of city living. The vitality of urban life, these critics claim, arises from innumerable small face-to-face encounters at street level: parents playing with children in parks, friends meeting on corners, shoppers brushing by and subconsciously assessing each other, etc. Thus it is no surprise that the contentious 1960s brought a classic confrontation between city planner Robert Moses, who wanted to bulldoze a 10-lane expressway through SoHo and Chinatown, and vocal opponents like Greenwich Village activist Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

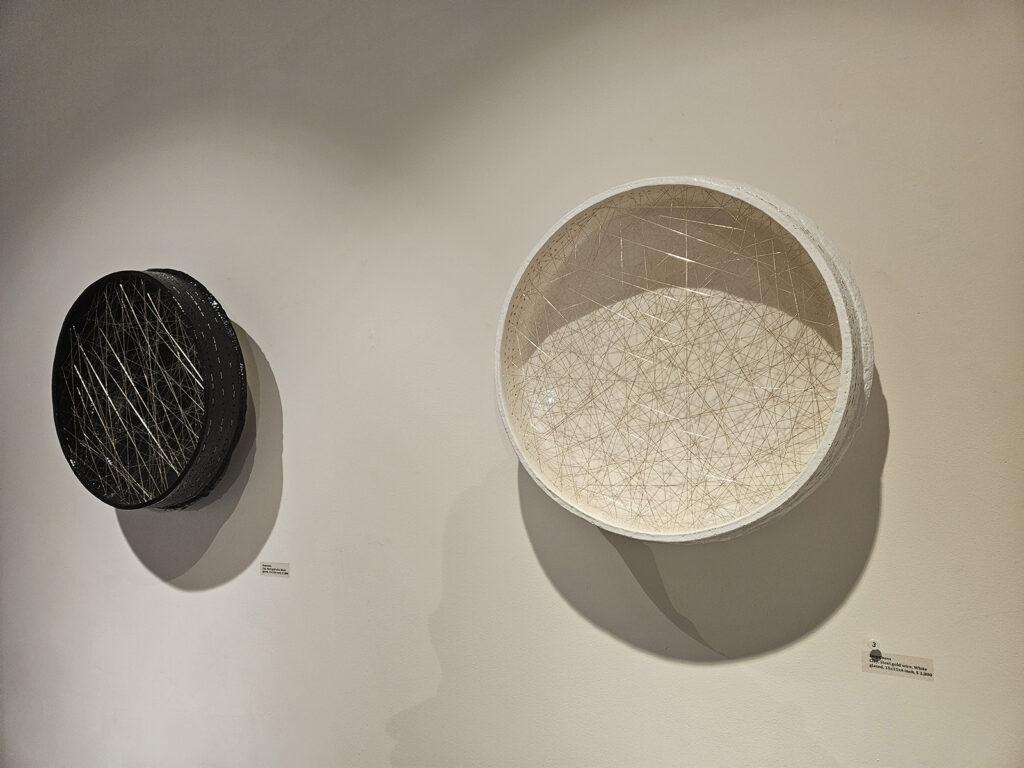

The other works shown in “Dreaming Desire” suggest that, for all Kang’s admiration for the twinkling city of dreams across the Hudson, her ultimate loyalty is to more intimate forms of human connection. The gallery’s walls and pedestals featured stylized bowl-shaped works, each with a central void crisscrossed by brass wires plated with gold or silver. While these wire meshes certainly bring to mind city streets seen from above, the individual strands passing through small holes in the vessel’s sides seem to hold the artwork together, conjuring associations with the strings of a musical instrument. One is reminded of the way families and communities are knit together by person-to-person “ties” and “bonds,” and of how those filaments, when correctly tuned, can produce social harmony. Kang’s shift of emphasis—from outer allure to inner tranquility—chimes with the admonition in Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach (1867):

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

In choosing interpersonal commitment as her theme, Kang connects with the entire history of her medium and craft. Pottery began as a way to convey sustenance (seeds, food, wine, oil) from one person to another. Pots are among the earliest artifacts of agriculture and communal living, the genesis of all higher civilization. Eventually, those vessels—and their derivatives, plates—facilitated mercantile exchange of their contents and then even became trade goods themselves, helping to knit the ancient world together through long-distance transactions and the intermingling of cultures that such commerce fosters. (Remnants of Greek amphoras and vases are found throughout the Mediterranean basin; Chinese porcelain was a sensation in 18th and 19th Europe.) Along the way, the finest ceramics evolved from utilitarian objects to decorative luxury items to pure works of art.

With the advent of avant-garde modernism, “finest” and “pure” no longer meant, as it had in previous centuries, the most refined designs and facture, the thinnest bone porcelain, the rarest glazes, the most intricate painted motifs, the most exquisitely fragile figurines. Instead, an appreciation of fractured forms and rough surfaces, and above all of concept, came to the fore. Kang, studying ceramics in Korea in the late 1980s, was aware of both the country’s long history of religious and courtly art, epitomized by perfectly shaped and smoothly finished moon jars, and its parallel tradition of “crude” but artfully made earthenware, loved for its material authenticity—a taste that extends even to broken-and-repaired plates and vessels, poignant reminders of the transience of all earthly things.

Clearly, Kang often simultaneously holds in her mind—and expresses in her art—two seemingly contradictory premises: the big city is glamorous, but domestic life is profoundly meaningful and sweet; ceramic works can offer pleasing shapes, gorgeous colors, and luscious surfaces, but they can also prod viewers into unsettling thoughts that need to be faced. That dual ability has made Kang one of the most prolific and significant Korean ceramicists in the United States. She has had 10 solo shows and participated in many group exhibitions. Her 40-year career is the realization of a childhood dream. As a young girl, visiting grandparents who lived near an abandoned kiln, she would make the old shards of pottery she found into playthings, imagining what life-stories the pieces represented: who had used them, and for what mysterious adult purposes or acts of indulgence? Later, when she encountered real working kilns, she was immediately and deeply fascinate by fire—seen not as a destructive force but as an agent of magical transformation. Eventually Kang was able to combine those two drives: taking up bits of clay, she combined and shaped them at the behest of an aesthetic concept, watching enthralled as lumpen earth changed into expressive artworks in her own skilled hands and her own fiery kiln.

Richard Vine is the former managing editor of Art in America magazine and the author of such critical studies as Odd Nerdrum: Paintings, Sketches, and Drawings (2001) and New China, New Art (2008), as well as the crime novel SoHo Sins (2016).

강종숙 : 꿈의 나라처럼

리처드 바인 지음

도예가 강종숙이 1994년에 처음 뉴욕에 왔을 때, 두 가지 시각적인 경험들이, 정말로, 의식적인 수준과 잠재의식적인 수준 모두에서, 갑자기 그녀의 마음에 각인되었다. 이 광경들은 그 이후로 그녀에게 있어 활발한 상상력의 원천으로 남아있다. 비행기 창문으로 본 첫 번째는, 교통으로 활기를 띠고 있는, 그 도시의 거대한 격자로 된 도로망이었다. 두 번째는 뉴저지에 있는 강종숙의 진정제가 있는 집 근처에서 허드슨 강 건너편으로 보이는 맨해튼의 고층건물들의 파노라마처럼 스치고 가는 광경이었다.

이 두 가지 모두 도시 밖에서 본 것이 적절하다는 것을 주목하라. 수 많은 새로운 도착자들은 바다나 공중에서 뉴욕에 착륙할 때 비슷한 흥분을 느꼈다. 그러나 대부분의 이민자들은 곧 눈부신 도시 경관에 몰입하여 요동치는 거리와 길 속에서 새로운 삶을 얻는다. 그러나 그것은 강씨의 것이 아니었다. 그렇다, 그녀는 서울과학기술대학교와 그 후 뉴저지의 몽클레어 대학에서 교육을 받은 예술가이지만 아내이자 어머니이기도 하다. 다른 위대한 중산층 한국인들처럼, 그녀는 조지 워싱턴 다리 서쪽의 비교적 안전하고 깨끗한 환경에 집을 마련했는데, 이는 흐리고 반짝이는 고담시티의 끊임없는 시야에서 아직 멀리 떨어져 있는 세상처럼 보인다.

그러나 이것은 좌절된 꿈들에 대한 단순한 이야기가 아니다. 강종숙은 그녀의 창조적인 에너지를 전달하기 위해 그녀의 사회적인 구속을 사용할 수 있었기 때문이다. 지난 30년 이상, 그녀는 특히 에덴의 지식의 나무, 곧 금지된 열매로 알려진 많은 종류의 도자기 사과를 포함하여 많은 작품을 만들었다. 알고 싶은 욕망이 아담과 이브를 단죄했을지 모르지만, 그것은 또한 그들에게 우리가 그것을 살고 있는 세계를 드러냈다. 그러므로 강종숙의 가장 최근 개인전이 “꿈꾸는 욕망”이라는 제목이 붙은 것은 우연이 아니다

이 쇼의 중심 작품은 10개의 3 ½ 피트 높이의 도자기 구조물을 설치한 것인데, 이것은 각 층 사이에 공간을 쌓아올린 직사각형 판들로 구성되어 있고, 내부에서 나오는 전기 빛을 보여준다. 이 조각물의 그룹은 해질녘 맨해튼의 사무실 블록들과 주거용 타워들처럼 잔잔한 빛의 투과 모습이었다. 세련되고 세계적인 삶에 대한 환상으로 가득한 강씨의 욕망의 이 조형물들은 갤러리 공간을 지배했고, 방문객들의 눈길을 지속적으로 끌었다. 그러나 그들의 매우 유혹적인 것과 자랑스러운 자기 주장은 곧 사람들로 하여금 그들의 침묵하는 주장에 의문을 품게 만들었다. 그 빛의 타워들은 르 코르뷔지에 고층 빌딩들로 이루어진 군집을 닮았으며, 이는 그 건축가의 래디언트 시티 계획과 다르지 않았다.

자비롭게도 파리의 중심지는 결코 건설되지 않았다. 윌리엄 H. 와이트와 같은 도시학자들은, 다수의 거주 공간을 수직 갱도로 끌어올리고, 모든 가게들과 그 사이에 있는 다른 저층 건물들을 치우고, 녹지대나 빈 콘크리트 광장을 만드는 것과 같은, 코르뷔지에의 건축 전략이 사실 도시 생활의 공격이라고 주장해왔다. 이러한 비평가들의 주장에 따르면, 도시생활의 활력은, 공원에서 아이들과 놀고 있는 부모들, 모퉁이에서 만나는 친구들, 쇼핑객들이 지나가거나 무의식적으로 서로를 평가하는 등, 길거리 수준에서 수없이 많은 작은 대면들로부터 발생한다. 그러므로, 논쟁의 여지가 있는 1960년대가 소호와 차이나타운을 통과하는 10차선 고속도로를 불도저로 만들려는 도시계획가 로버트 모제스와 위대한 미국 도시의 죽음과 삶의 작가인, 그리니치 빌리지 운동가 제인 제이콥스와 같은 목소리를 내는 반대자들 사이에 고전적인 대결을 가져온 것은 놀라운 일이 아니다.

“꿈꾸는 욕망”에 나타난 다른 작품들은 허드슨 강 건너 반짝이는 꿈의 도시에 대한 강씨의 동경에도 불구하고, 그녀의 궁극적인 충성심은 인간관계의 보다 친밀한 형태에 대한 것임을 암시한다. 갤러리의 벽과 받침대들은 양식화된 그릇 모양의 작품들을 특징으로 하며, 각각 금이나 은으로 도금된 놋쇠 와이어로 교차된 중앙의 공극을 가지고 있다. 위에서 본 도시의 거리들을 확실히 연상시키는 반면, 배 측면의 작은 구멍들을 통과하는 각각의 가닥들은 이 작품을 하나로 묶는 것처럼 보이며, 이는 악기의 현과 연관성을 연상시킨다. 한 사람은 가족과 공동체가 개인 대 개인의 “연분”과 “연분”에 의해 서로 엮이는 방식과, 이 필라멘트들이 올바르게 조정되었을 때, 어떻게 사회적 조화를 이룰 수 있는지를 상기시킨다. 외적인 유혹으로부터 내적인 평온으로의 강씨의 전환은 매튜 아놀드의 “도버 비치” (1867)에서의 방향제시와 일치되고 있다:

아, 사랑, 우리 진실하자

서로에게! 세상을 위해

꿈의 나라처럼 우리 앞에 누워있고,

다양하고, 아름답고, 새롭고,

기쁨도 사랑도 빛도 없다,

또한 확실한 것도, 평화도, 고통을 돕는 것도 없습니다;

대인관계의 헌신을 그녀의 주제로 선택함에 있어서, 강씨는 자신의 매체와 공예의 모든 역사와 연결된다. 도자기는 한 사람에게서 다른 사람으로 생계 (종자, 음식, 와인, 기름)를 전달하기 위한 방법으로 시작되었다. 냄비는 모든 고등 문명의 시초인 농업과 공동 생활의 초기 공예품들 중 하나이다. 결국, 그 그릇들과 그 파생품들, 접시는 그 내용물의 상업적 교류를 촉진하고 나아가 무역품 그 자체가 되어 먼 거리의 거래와 그러한 무역이 육성하는 문화의 혼합을 통해 고대 세계를 하나로 묶는 데 도움을 주었다.

(그리스의 암포라와 화병의 잔재는 지중해 유역에서 발견되며 중국의 도자기는 18, 19세기 유럽에서 센세이션을 일으켰다.) 그 과정에서 최고급 도자기는 실용적인 물건에서 장식적인 사치품으로, 순수한 예술 작품으로 진화했다.

아방가르드한 모더니즘의 출현으로, 이전 세기에 그랬던 것처럼, “가장 가는”과 “순수한”은 더 이상 가장 세련된 디자인과 제작, 가장 얇은 뼈로 된 자기, 가장 희귀한 유약, 가장 정교한 채색 모티프, 가장 절묘하게 연약한 조각상을 의미하지 않았다. 대신에, 골절된 형태와 거친 표면, 그리고 무엇보다도 개념에 대한 감상이 전면에 나왔다. 1980년대 후반 한국에서 도자기를 공부한 강씨는 완벽한 모양과 매끄럽게 마감된 달항아리로 전형화되는 종교적이고 궁중 예술의 오랜 역사와 “조잡한” 그러나 예술적으로 만들어진 토기의 평행한 전통, 깨지고 수리된 접시와 그릇에까지 확장되는 맛, 이 지상적인 모든 것의 과도함을 가슴 아프게 상기시키는 재료적인 진정성으로 사랑을 받았다.

분명히, 강씨는 자주 그녀의 마음속에 – 그리고 그녀의 예술에 표현한다: 거대한 도시는 화려하지만, 가정 생활은 매우 의미 있고 달콤하다; 도자기 작품들은 기분 좋은 모양, 아름다운 색, 그리고 감미로운 표면을 제공할 수 있지만, 그것들은 또한 직면해야 하는 불안한 생각들로 시청자들을 자극할 수 있다. 그 이중적인 능력은 강씨를 미국에서 가장 다작하고 중요한 한국 도예가들 중 한 명으로 만들었다. 그녀는 10회의 개인 전시회를 가졌고 많은 단체 전시회에 참가했다. 그녀의 40년 경력은 어린 시절 꿈의 실현이다. 어린 소녀였을 때, 버려진 가마 근처에 살고 있던 조부모님들을 방문하여, 그녀는 도자기의 오래된 조각들을 놀이로 만들었으며, 그것들을 누가 사용했는지, 그리고 어떤 신비한 성인의 목적이나 탐닉 행위를 위해 그것들을 표현했는지를 상상했다. 나중에, 그녀가 진짜 노동용 가마를 만났을 때, 그녀는 즉각적이고 깊은 불에 매료되었는데, 이것은 파괴적인 힘이 아니라 마법을 바꾸는 작용을 하는 것으로 보였다. 결국 강씨는 그 두 가지 추진력을 결합할 수 있었다: 흙 조각들을 집어 들고, 그녀는 미적 개념의 요청에 따라 그것들을 결합하고 모양을 만들 수 있었고, 뭉친 흙이 그녀의 숙련된 손과 자신의 불타는 가마에서 표현적인 예술작품으로 변화하는 것을 지켜보았다.

Richard Vine은 Art in America 잡지의 전 편집장이자 범죄 소설 소호 신스(Soho Sins, 2016) 뿐만 아니라 Odd Nerdrum: Paints, Sochets and Draws (2001), New China, New Art (2008)와 같은 비평적인 연구의 저자이다.

이 쇼는 2023년 11월 2일부터 12월 8일까지 뉴저지주 포트 리에 있는 파리스 고 파인 아트(Paris Koh Fine Arts)에서 전시되었다.

Richard Vine is the former managing editor of Art in America magazine and the author of such critical studies as Odd Nerdrum: Paintings, Sketches, and Drawings (2001) and New China, New Art (2008), as well as the crime novel SoHo Sins (2016).

Jongsook Kang: Dreaming Desire

by Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos

Jongsook Kang’s two-part series Emptiness and Dreaming Desire, presented together at this solo exhibition, manifest the artist’s innermost spiritual and mundane experience undoubtedly manifesting the secret nucleus of her ceramic sculpture in the last twenty years; namely New York/Seoul cities and Eastern Philosophy. Deeply inspired by the mystical teachings of Śūnyatā of Japanese Zen Buddhism, Kang imports a reflective quality that conveys silent introspection by interweaving a nexus of gold, silver, black and copper wires throughout her pieces that faintly recall the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi but also the Korean philosophy of emptiness as fulness called bium. By so doing, she ritually metamorphosizes her objects into memory vestiges of human social networks or relationships in her beloved cities New York or Seoul. These ceramic edifices can be read in terms of the isolation felt during the Covid-19 pandemic, or in general as the loneliness of city life. Simultaneously, they can be seen as reconstructions associated with objects and mnemonic taboos – a transcended net of intertwined potentialities withdrawn from our a-priori forms of time and space – for the deceased victims of the Corona virus crisis.

Furthermore, Kang’s delicate layers of clay, which vaguely recall Seoul’s or New York’s towering skylines casually observed from across the banks of Hudson or Han Rivers, deliberately function as metaphors and concrete incorporations of Confucian ontological principles. This philosophy is combined with Daoist aesthetics in Korea to formulate ideas of the yin and yang which represents the opposing yet similar principles of dark/light, feminine/masculine, action/inaction, dark and light in cosmic harmony.

Kang skillfully handles physical and architectural space through the precise use of artificial lighting as a metaphysical duality of substantial positivity or negativity (as in in yin-yang Taegeuk philosophy). Moreover, the artist consciously transfigures her skyscraper-like constructions of square plates into imaginative comments about the ever-growing solitude of everyday life, principally experienced in global metropoles like New York or Seoul. Through her sculptures Kang also comments upon the eternal continuation of incessant change in a hectic world of constant becoming. As she laconically wrote in her artist’s statement: “in other words, my sculptures embrace the possibility of countless changes, and infinite possibilities that lead to eternity. The realization of the true colors of yin and yang, in which the eternity of light is condensed, can be said to be my own Dream-Desire”.

Many German philosophers or psychologists of 19th and 20th century Sigmund Freud for example, firmly believed that desire is the inner drive that substantially formulates every human being, while always being dynamic and tenuously alternating between objects and needs. While concurrently eternal and torturously unceasing like a strong current, desire undeniably (re)defines the unique individuality of each and every life form on the planet. Kang’s Dreaming Desire powerfully constitutes the polymorph matrix of opposing desires, in which frenetic life and spiritual emptiness or receptive yin and active yang harmoniously co-exist together despite their existential dissimilarities and internal struggles.